Physicians say demands of the profession compete with desire to have a family

In the first of a two-part series, we explore the issues and complexities of balancing a fulfilling career in medicine and having a family. This series was inspired by a response from a member to our story intake form. Read part two here.

In the world of medicine, preparing to have a family while advancing a career is a common dilemma. From carving out time for dating to planning a pregnancy, finding balance remains a perpetual challenge.

In the world of medicine, preparing to have a family while advancing a career is a common dilemma. From carving out time for dating to planning a pregnancy, finding balance remains a perpetual challenge.

For many physicians, their all-consuming career can become a roadblock to fully realizing a dream others may take for granted.

Dr. Maxime Billick knew early on in life that she wanted to have children, but struggled to find time to pursue a relationship while she finished her residency. Dr. Billick, a 36-year-old infectious diseases fellow graduating soon from the University of Toronto, found that residency life provided few opportunities to date or meet potential partners, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dr. Maxime Billick knew early on in life that she wanted to have children, but struggled to find time to pursue a relationship while she finished her residency. Dr. Billick, a 36-year-old infectious diseases fellow graduating soon from the University of Toronto, found that residency life provided few opportunities to date or meet potential partners, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It’s hard sometimes to go on dates because you’re on call for 26 hours, or you’re in the hospital or you’re on call the next day and you don’t want to stay up too late,” she said.

When she turned 34, Dr. Billick knew she had to start thinking about planning for children. After doing some research and speaking to friends and colleagues with experience in the matter, she decided to freeze her eggs.

Dr. Maxime Billick, an infectious diseases fellow graduating soon from the University of Toronto.

The decision made her feel empowered and less anxious. Though she has since met and become engaged to her partner, she feels there is less of a “ticking time bomb” dictating when she must make reproductive choices.

“And while there still is certainly some time limitations, I felt like it allowed me a little bit more freedom to relax and think a bit more creatively about what having a family would look like,” Dr. Billick said.

She has spoken to fellow doctors who have expressed wistfulness in not prioritizing family planning sooner. In her case, she had a mentor – her supervisor at work – who was extremely supportive of her plan to freeze her eggs.

“He said, ‘100 per cent, take the time you need,’ and I think that just really highlights the importance of having an ally in that space,” she said.

She was chief medical resident at Toronto General Hospital the year she froze her eggs, a position that allowed her some flexibility for appointments. And she had a small office with a couch, where she could take breaks in the days after the procedure.

For many medical students, residents and physicians, it can sometimes feel like there isn’t a right time in the early stages of their career to prioritize having a family, said Dr. Shirin Dason, a reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialist at TRIO Fertility clinic in Toronto.

For many medical students, residents and physicians, it can sometimes feel like there isn’t a right time in the early stages of their career to prioritize having a family, said Dr. Shirin Dason, a reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialist at TRIO Fertility clinic in Toronto.

While residency can be an ideal time to have a baby because of the availability of paid parental leave and a lack of a practice patient load, many students want to enter the workforce as soon as possible to start paying off their medical school debt.

Delaying parenthood until a doctor is in practice can come with its own difficulties. That includes finding a locum who can take over during a physician’s maternity or parental leave – a problem exacerbated by the current crisis in primary care.

“It is a huge added stress,” she said.

Dr. Shirin Dason, is a reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialist at TRIO Fertility clinic in Toronto.

Dr. Dason, 33, and her husband conceived their two children during her residency via IVF due to infertility unrelated to age. She has talked to many physicians who lamented that they were only able to take a few weeks or months off to be with their child because they felt they couldn’t leave their clinic or practice for a longer period.

“I speak from the subspecialty viewpoint, but it’s even tougher on primary care physicians, as we know now,” said Dr. Dason, who just completed a gynecologic reproductive endocrinology and infertility fellowship at Mount Sinai Fertility in Toronto.

“The pressures are so immense because we are all expected to work at a capacity that we cannot possibly sustain.”

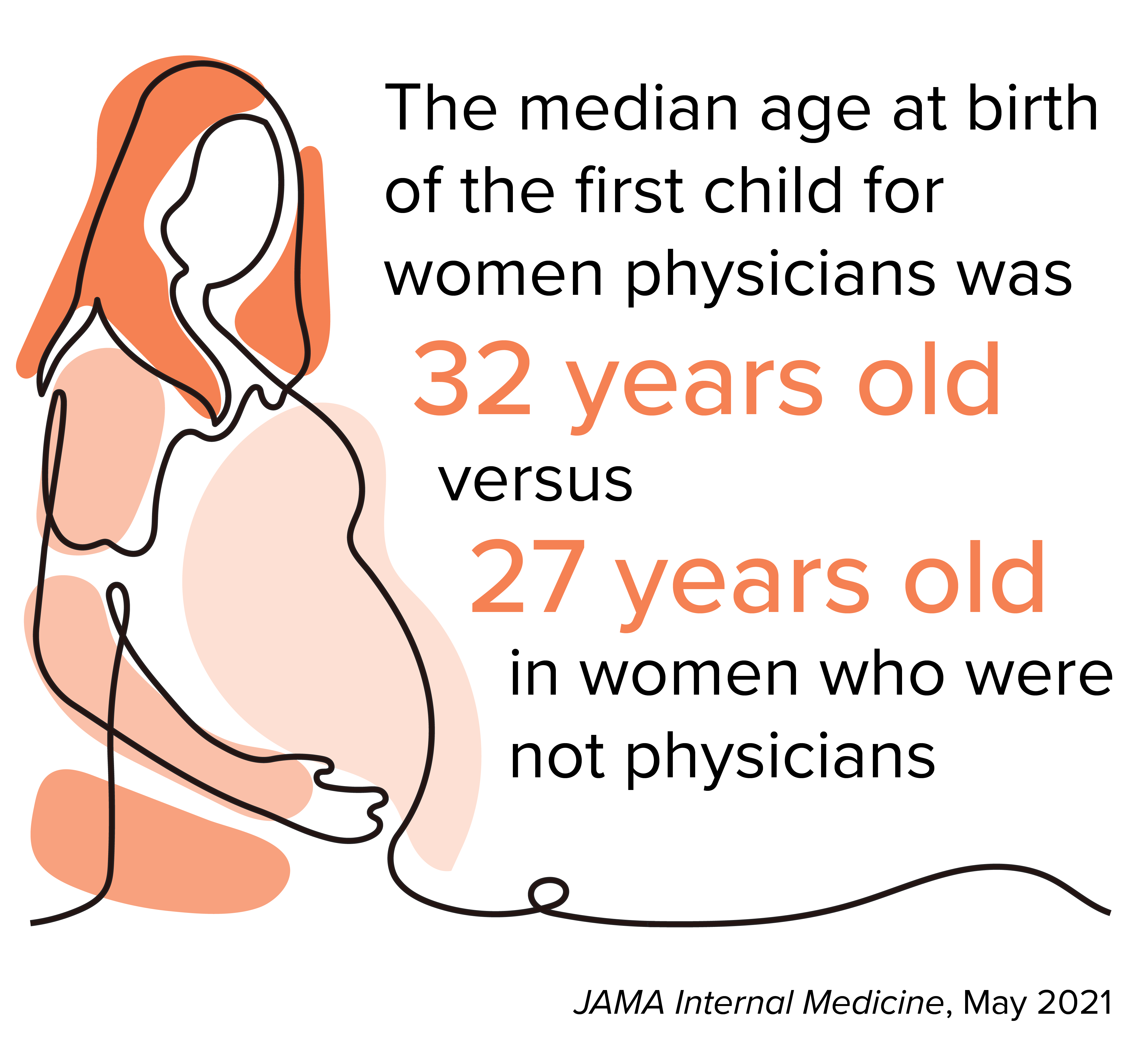

A study of reproductive-aged women in Ontario published by JAMA Internal Medicine in May 2021 found that women physicians were less likely to give birth at a younger age and initiated childbearing significantly later than non-physicians.

A study of reproductive-aged women in Ontario published by JAMA Internal Medicine in May 2021 found that women physicians were less likely to give birth at a younger age and initiated childbearing significantly later than non-physicians.

The study compared the childbirth outcomes of 5,238 licensed physicians of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario to those of 26,640 non-physicians. It followed reproductive-aged women between 15 and 50, with data gathered between 1995 and 2018.

The women who were not physicians were drawn from the ICES Registered Persons Database, which contains information on persons registered under the Ontario Health Insurance Plan.

The study found that the median age at birth of a first child for the women physicians was 32 years old versus 27 years old in the women who were not physicians. After organizing for specialty, the study found that family physicians had a higher rate of giving birth than both surgical and non-surgical specialists at all observed ages.

The age gap between physicians and non-physicians is concerning for Dr. Dason as a fertility specialist.

“We know that fertility declines with time and that the chance of having the full family that you’ve always wanted after the age of 40 becomes much more difficult,” she said.

Part of the issue is the demands in medicine and the profession’s culture.

It can, for example, make single parenthood a daunting prospect, said Dr. Billick, resulting in many physicians choosing to wait until they can find a partner and build a more traditional family structure.

She said there are also aspects of medical culture that need to change to make pursuing parenthood a valid option for all, including battling stereotypes that are harmful to everyone.

“Women are seen as caregivers, so maybe they get a little bit more of a pass when they have to go pick their kid up or when they’re sick for a day,” Dr. Billick said.

“But when male residents have to stay home because their kid is sick or maybe they’re feeling particularly emotional because something didn’t go well in IVF, that’s not really validated in the same way.”

This culture can also impact the paths students choose in residency and beyond, said Dr. Dason. Residents would hear anecdotes about what’s possible in certain specialties.

“Things like, ‘you can’t be a surgeon if you’re going to have a family’,” she said. “That would make them think, ‘Oh, well, I want a family so I can’t be a surgeon’.”

Small comments like this, however casual, can stick with trainees as they make choices that will impact the rest of their career. Women were particularly discouraged by them. She was fortunate to have mentors of all genders who had prioritized having a family while pursuing a full career.

While completing her fellowship at Mount Sinai, the team Dr. Dason was part of interviewed final-year medical students about their perspectives on family planning in medicine.

The team published their study in JAMA Surgery in December 2023. They found medical students had a general perception that family building during training may have unfavourable implications for team dynamics and relationships with colleagues.

Students interviewed for the study felt that there is no ideal time in a medical career to build a family; that family planning is a taboo topic; that surgical specialities offer less support for family building; and that residents who have children are perceived to be placing a burden on their colleagues. The students also said they considered their family goals when choosing a specialty.

The team then created a resource for physicians, especially trainees, to help answer their questions about creating a family plan while building careers.

The website, familyplanningfordocs.com, features a number of resources, including:

The team wanted the website to answer questions that medical students, residents and physicians may not have considered.

“What are the different financial options in residency for parental leave? What are the different financial options when I’m a staff? What are the different pressures?” Dr. Dason said.

She is now working on a separate study that involves speaking to residents about these issues.

“I think that sometimes when we go into medicine, we don’t fully appreciate what sort of dedication we are committing ourselves to,” she said. “It seems like there’s this very prescribed pathway of what you have to do and how you have to get there, and sometimes we forget that it’s a journey in and of itself.”

Next week: In the second of this two-part series, we explore the difficulties in securing a full maternity leave as a physician, and how the culture of medicine introduces barriers to prioritizing parenthood.

Jessica Smith is an OMA staff writer.