This article originally appeared in the Spring 2022 issue of the Ontario Medical Review magazine.

New model would move procedures into publicly funded ambulatory centres

Millions of Ontarians are waiting for backlogged surgeries and procedures. Many are frustrated, in pain and their condition may be deteriorating. Some may be depressed or anxious and unable to cope. Their lives are on hold.

For both surgeons and proceduralists, the greatest professional reward there can be is operating on and saving the life of a patient. And there can be few frustrations greater than not being able to fit other patients into your schedule, knowing they are suffering as a result. Dr. Najma Ahmed, chief of surgery at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, has known both the rewards and the frustrations. She says the system rightly prioritizes urgent patients, but too often at the expense of less urgent but still important cases.

“I, and many other surgeons I work with have had long waiting times for our patients, particularly for less urgent, non-life-threatening problems,” Dr. Ahmed said. “The thing is, though, surgery for those patients is life-sustaining. It improves their quality of life and decreases their morbidity and mortality over time. They need these surgeries. We need to develop a solution that ensures that these operations can be done safely and efficiently.”

Wait times have bedevilled governments and health-care systems for decades. In Ontario, successive governments have grappled with the problem of long surgical wait times and frustrating delays in care, with limited success. While the wait times problem pre-dated COVID-19, there is no question that the pandemic shone a harsh light on Ontario’s inability to meet the surgical and procedural needs of all its patients in a timely manner. And COVID-19 made the problem much worse.

Wait times have bedevilled governments and health-care systems for decades. In Ontario, successive governments have grappled with the problem of long surgical wait times and frustrating delays in care, with limited success. While the wait times problem pre-dated COVID-19, there is no question that the pandemic shone a harsh light on Ontario’s inability to meet the surgical and procedural needs of all its patients in a timely manner. And COVID-19 made the problem much worse.

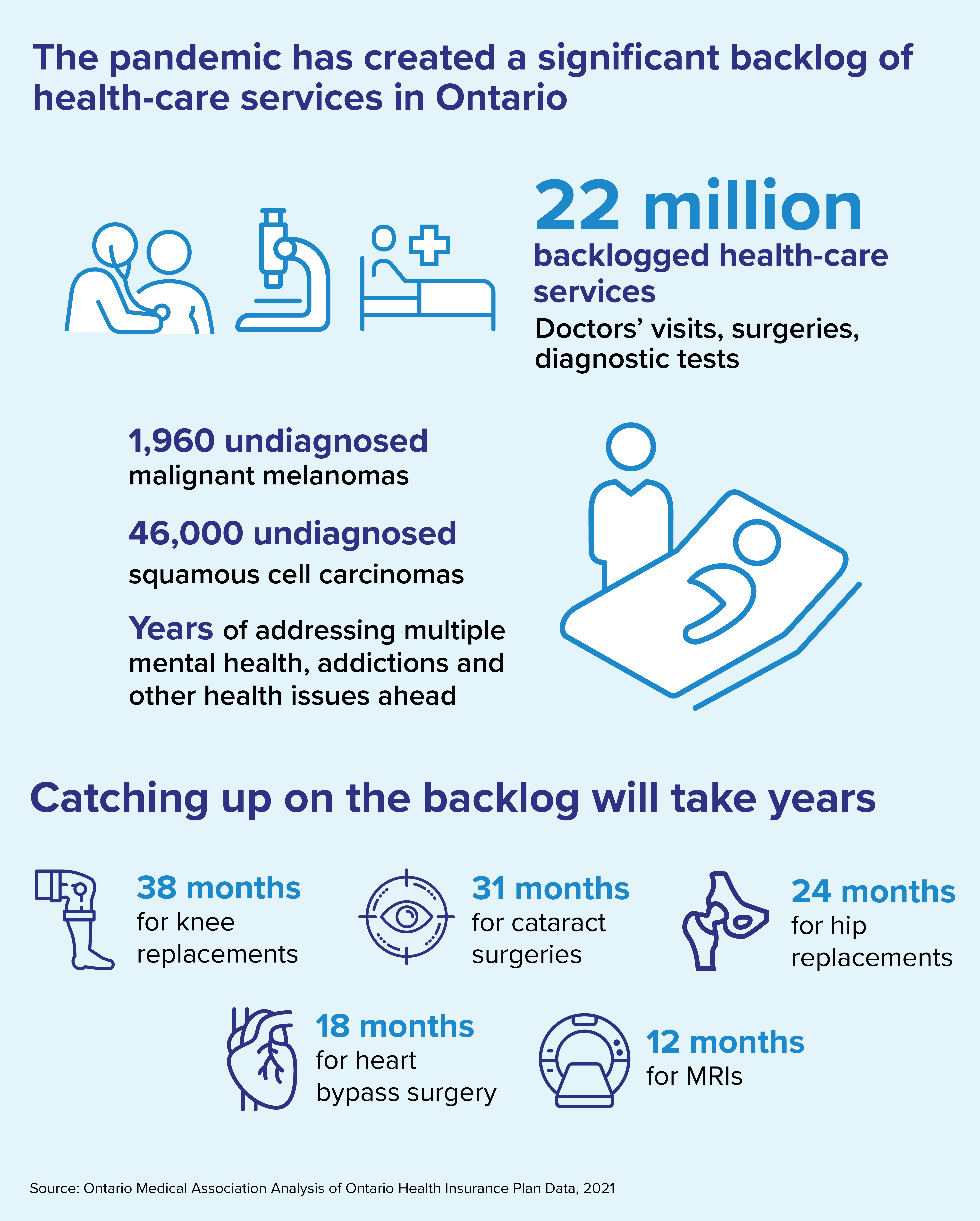

The pandemic has created a backlog of more than 21 million patient services, according to an analysis by the Ontario Medical Association. This daunting list of undelivered but necessary services includes more than one million surgeries and procedures, as well as preventive care procedures, cancer screenings such as mammograms and colonoscopies, and diagnostic tests such as MRIs and CT scans. The current backlog will take months and in some cases years to clear, and given that the pandemic has not yet run its course, the problem will likely continue to grow.

Photo: Dr. Najma Ahmed, chief of surgery at St. Michael’s Hospital, remarks that the health-care system’s prioritization of urgent care patients leaves other patients behind with worsening conditions.

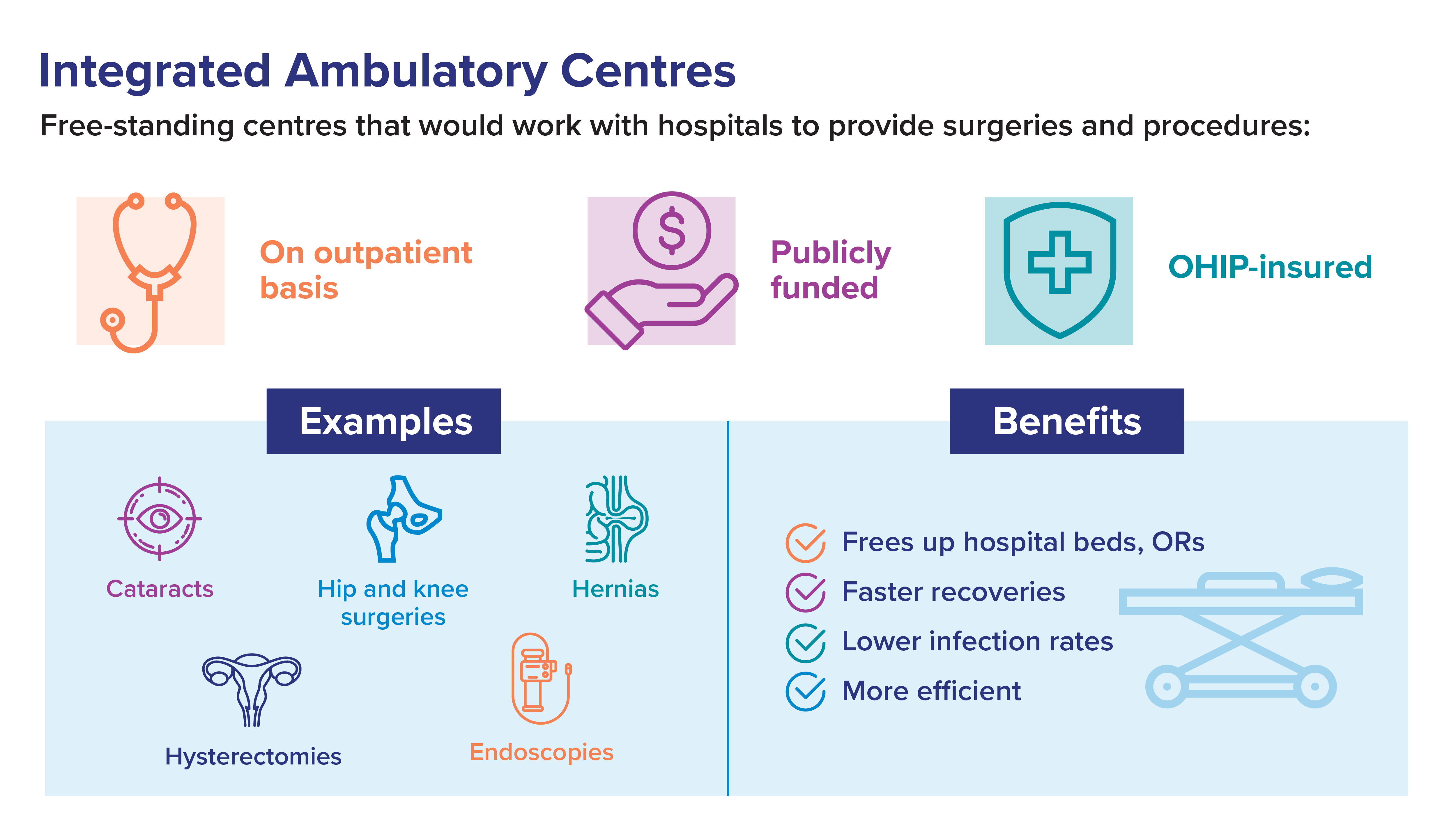

To tackle the wait time crisis in Ontario, the OMA unveiled a report in February recommending a new model of care that would focus on moving less complex surgeries and procedures out of hospitals and into what the organization is calling Integrated Ambulatory Centres.

The report, Integrated Ambulatory Centres: A Three-Stage Approach to Addressing Ontario’s Surgical and Procedural Wait Times, recommended that these publicly funded, free-standing centres work in partnership with local hospitals, with the hospitals retaining the more urgent and acute cases.

The ambulatory centres would deliver specialized services such as cataract surgeries, hernia repairs, hysterectomies, hip and knee surgeries, endoscopies, ear, nose and throat surgeries and breast reconstruction after breast cancer. The surgeries and procedures would continue to be paid for by OHIP.

The ambulatory centres would deliver specialized services such as cataract surgeries, hernia repairs, hysterectomies, hip and knee surgeries, endoscopies, ear, nose and throat surgeries and breast reconstruction after breast cancer. The surgeries and procedures would continue to be paid for by OHIP.

The proposal, developed in association with consultants Santis Health, was informed by consultations with a wide range of physicians, health-care leaders, clinical experts and key system stakeholders. Dr. Jim Wright, chief of OMA Economics, Policy and Research, initiated and spearheaded the initiative.

He said the ambulatory care model has been successfully adopted in other jurisdictions, and even in Ontario there have been precursors such as the Kensington Eye Institute that have worked extremely well. Ambulatory centres have faster recovery times, lower infection rates and efficiency gains ranging from 20 to 30 per cent compared with inpatient hospital care, Dr. Wright said.

“You have a bunch of cases, they need to be done somewhere, so why wouldn’t you want them done faster, more efficiently and with similar or better quality than in a hospital? You don’t go to a hospital to get your dental treatment. You get that done in a dentist’s office, because he or she is perfectly ready to manage what your needs are in that setting.”

The OMA report says research has found that patients waiting for surgery often experience chronic pain, which has been linked to decreased quality of life, increased comorbidities such as anxiety and depression and increased susceptibility to substance use disorders. The report quotes one study that found that patients who wait more than six months for joint replacement surgery have a 50-per-cent greater chance of worse outcomes, including more pain and difficulty with functional activities after surgery.

Dr. Wright said the benefits associated with doing more surgeries in ambulatory centres are clear and numerous. Patients can expect shorter wait times for surgeries and procedures, high quality care and better access to specialists, as well as increased convenience. Health professionals will experience less burnout and improved inter-professional collaboration. Pressure on hospitals will be reduced, and they will see increased capacity over the long term because of their partnerships with Integrated Ambulatory Centres.

Ontario has had independent health facilities for more than 30 years, but they have not adapted to the shifting needs of Ontario’s patients and are mainly licensed for diagnostics such as X-rays and ultrasounds.

“I have had long waiting times ... particularly for less urgent, non-life-threatening problems. We need to develop a solution that ensures that these operations can be done safely and efficiently.” —Dr. Najma Ahmed

Dr. Wright emphasized the focus on integration in the new model. Integrated Ambulatory Centres would not operate in a siloed manner but would partner with local hospitals and be fully integrated into Ontario’s regional health systems. Quality control standards would be the same in hospitals and Integrated Ambulatory Centres, with a focus on sharing best practices, and co-operation and co-ordination, ensuring that the funding formula does not disadvantage hospitals. The OMA proposal fully complies with the principles and guidelines of the Canada Health Act and there would be no user fees or queue-jumping.

What there would be is a vast improvement in the way care is delivered to patients, Dr. Wright said.

What there would be is a vast improvement in the way care is delivered to patients, Dr. Wright said.

“If you can separate inpatient and outpatient surgeries, you achieve efficiencies and possibly quality that you just can’t achieve consistently in an acute-care institution that mixes those two streams,” Dr. Wright said. “I’m not saying hospitals should completely get out of the ambulatory care business, but I’m saying the vast majority of those procedures should be done in ambulatory care centres, which are designed to look after those patients effectively and efficiently.”

The OMA is proposing a three-stage approach to the adoption of this new model, spanning five to eight years. The first stage would focus on expanding capacity within existing system structures, laying a solid foundation for beginning to shift more care into ambulatory settings. A significant priority during this first stage must be resolving the problem of health-care provider shortages.

The second stage would see the building of necessary infrastructure to allow for an efficient, regionalized approach to surgical and procedural management in the new ambulatory centres. This would include introducing new legislation to allow for the creation of Integrated Ambulatory Centres, as well as launching regional calls for partnerships interested in setting up centres.

Finally, stage three would see the model come to life. The OMA expects the first new Integrated Ambulatory Centres could open within five to eight years, depending on required changes in legislation and where the centres would be located. Meanwhile, some existing independent health facilities would transition to Integrated Ambulatory Centres in a phased manner within 24 months.

Photo: With Ontario’s increased backlog of surgeries, Dr. Jim Wright, chief of OMA Economics, Policy and Research, recommends the province adopt an ambulatory care model, allowing hospitals to catch up on more urgent cases.

It is expected that by the time stage three is underway, the province’s new Ontario Health Teams would have evolved to the point where they can play a key role in ensuring provider partnerships and a smooth patient experience. Patients would begin receiving seamlessly integrated care thanks to joint care planning and care delivery between Integrated Ambulatory Centres, hospitals, primary care, rehab, home and other community care centres.

Dr. Wright said he believes this new model is the right one for patients, providers and the province. But it will take commitment and money.

“Right now, there are critical resources shortages, particularly of nurses. So, the first thing we have to do is invest in the existing structure. Let’s get additional monies to those areas of highest need. Let’s use what we have and try and do it most efficiently within that context. Once we’ve stabilized and have the people we need in place, we can build towards these Integrated Ambulatory Centres.”

Once the centres are in place, the biggest winner may be the health-care system overall. The OMA proposal has the potential to help solve a decades-old wait-times problem. In addition, it would be fulfilling its essential mandate to Ontario patients, which is to provide them with the highest quality care, in the quickest and most convenient way possible.

“Ambulatory centres have faster recovery times, lower infection rates and efficiency gains ranging from 20 to 30 per cent compared with inpatient hospital care.” —Dr. Jim Wright

Dr. Najma Ahmed agreed with Dr. Wright about the benefits of the OMA proposal, though her attitude might best be described as one of cautious optimism.

“You know, the health-care system is not what you’d call agile. Changing it is like trying to turn an ocean tanker,” Dr. Ahmed said. The health-care system is risk-averse but that is because safety must be a key priority, she added. “It’s about selecting the right patient, the correct surgery and assuring a high degree of integration and collaboration with local hospitals.”

Creating a new care model will require a significant financial investment and a lot of political will, she said. “But we’ve been thinking about this for 30 years now. Time to get it done.”

Colin Gray is a Toronto-based writer.